A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE HIGH SCHOOL OF FASHION INDUSTRIES: REFLECTING THE HISTORIES OF IMMIGRATION, THE GARMENT INDUSTRY AND UNIONISM IN NEW YORK CITY

After World War I, the garment industry was the largest employer in New York City. In 1928, its workers earned four billion dollars (the budget for the City of New York was only 520 million). But the industry had a major problem. Prior to World War I, almost all its workers were immigrants from Eastern or Southern Europe. After the war, restrictive immigration laws were passed cutting off this supply of workers. If it were to survive, the industry would have to train new generations of workers.

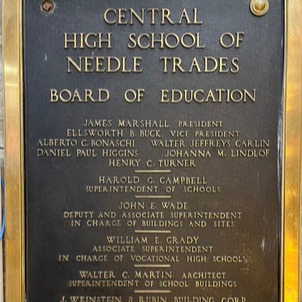

In 1926, educator Mortimer C. Ritter, aided by industry mogul Max Meyer, started Central Needle Trades High School in two classrooms located in a factory loft on West 31st Street. In a few years, it outgrew this venue, making use of dozens of classrooms in a former elementary school on 24th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues.

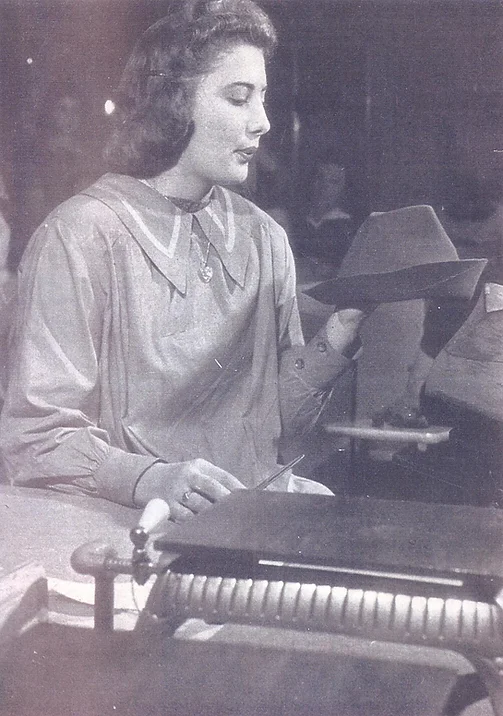

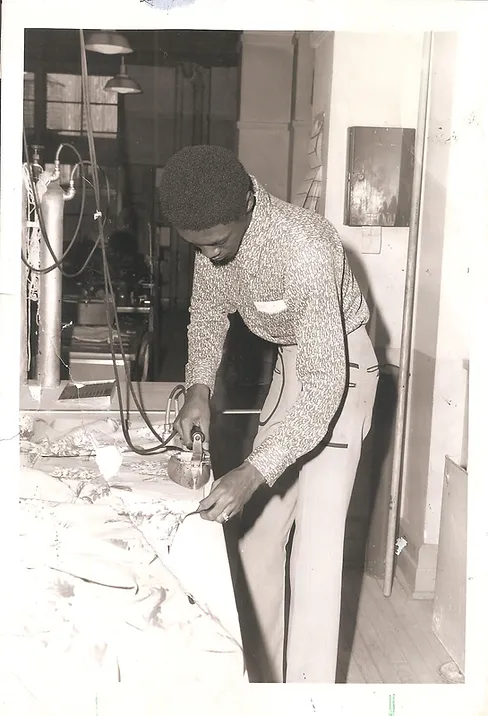

At this time, Central Needle Trades was considered an “extension school.” Boys and girls, fourteen to eighteen were released from their jobs for part of the day each week to enhance their occupational skills and learn basic English, mathematics, hygiene and civics. With the garment industry wanting workers with more than an elementary school education, by 1936 Central Needle Trades began to resemble a traditional four-year high school, albeit with 75% of class time devoted to trade related subjects.

Such was the importance of the garment industry to the economy of the city. That same year, the City Council authorized the expenditure of 3.5 million dollars to build a new school. When he laid the cornerstone to the new building, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia praised it, saying it would be “a model school in the field of education.”

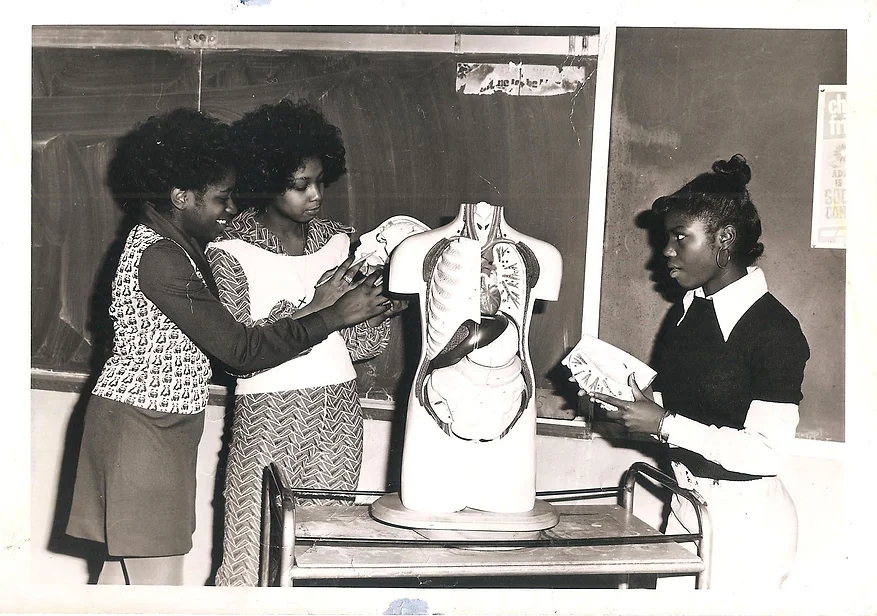

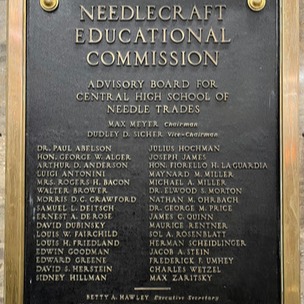

This “skyscraper building” would house model shoe, fur and clothing factories on a miniature scale. Here, students would learn to become cobblers, tailors and furriers “under scientific tutelage amid pleasant surroundings” (The New York Times 12/11/1938, p. 73). Given the origins of the school, many of the industry and union leaders on the school’s Advisory Board were immigrants: Max Meyer from Prussia, David Dubinsky (President of the ILGWU) from Poland, Nathan Orbach (founder of Orhbach’s department stores) from Austria, Sidney Hillman (President of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers) from Lithuania.

The 10-story building opened in January,1940 and was officially dedicated that June. Its design mirrored the dozens of other garment industry buildings on the Lower West Side, with retail outlets on the first floor (the school had menswear, ladieswear and shoe stores that sold wares made by students) and manufacturing workshops above. Most of the student body was comprised of the children of immigrants looking for their share of the American Dream through careers in the garment industry.

A centerpiece of the new building was a state-of-the-art auditorium (at the time, the largest entertainment venue on the West Side) with its now New York City landmark murals. These murals depict the rise of the union movement within the garment industry, spurred by the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire and leading to an era of cooperation between unions, management, and government through President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. In many ways, the school itself is a monument to this cooperation.

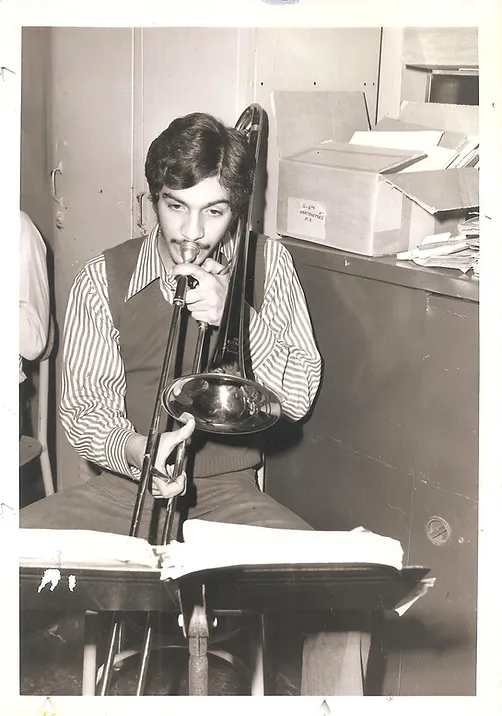

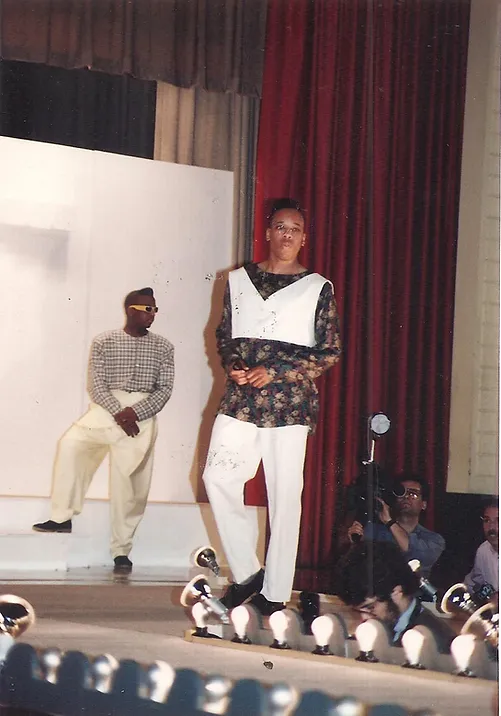

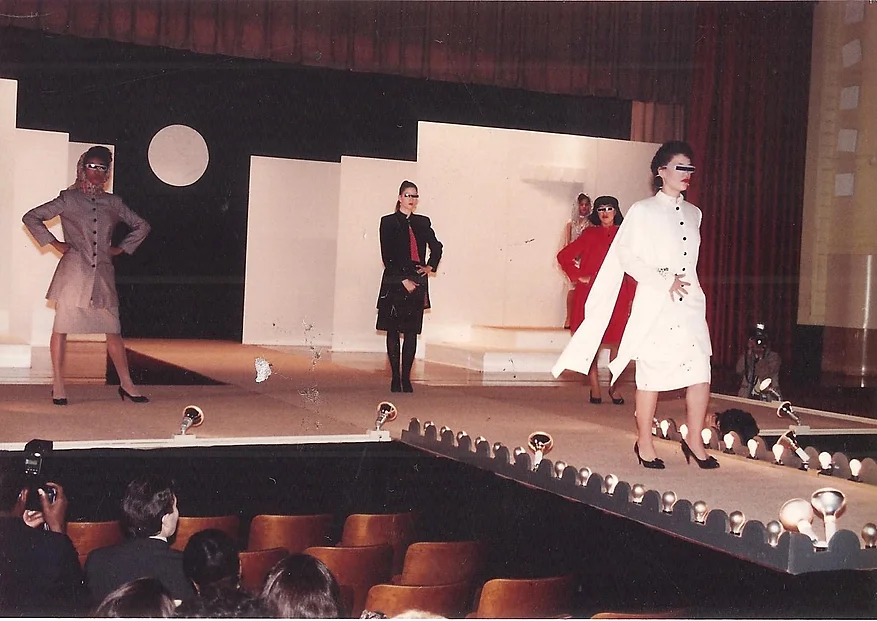

Over the years, this auditorium has served many purposes. In 1946, a fledgling Ballet Society, choreographed by George Balanchine, presented its first season on the stage; it would later become the American Ballet Theater. In the 1950’s, it was a cinema art house, showing European classics on Wednesdays and weekend evenings. Many entertainers performed there, from Sammy Davis, Jr. to Aretha Franklin to original cast members of Les Misérables. Politicians addressed audiences there, including mayors Fiorello La Guardia and David Dinkins and presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Bill Clinton. And, of course, there were dozens of fashion notables, such as Tommy Hilfiger, Tim Gunn and Joseph Abboud.

In 1944, the upper three stories of the new building housed “a post high school institute” for graduates who wanted to continue their education. By 1951, this was a state-chartered community college that would become the Fashion Institute of Technology. Principal Ritter also served as the first President of F.I.T. In 1959, F.I.T. moved to its own building on West 27th Street.

The 1940s were a turbulent time with the rise of Fascism, World War II, the beginnings of the Cold War, and a new wave of immigrants fleeing from the Iron Curtain. The yearbooks of the time document the contributions of the school to the war effort, from purchasing and donating an ambulance to the armed forces, to making parachutes and uniforms, to students leaving school to serve overseas. In his message to the graduates of 1944, Principal Ritter, echoing President Roosevelt, wrote: "Today, powerful foes of equality and liberty are hard at work to disrupt the Union . . . to divide and conquer . . . by pitting man against man, Christian against Jew, Negro against White. Be on guard against those who attack others because they have foreign-sounding names. Be on guard against those who disseminate false racial theories which deny the equality of man’s birthright and set man against man according to the color of his skin or the religion of his fathers. We are fighting for freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, freedom from fear. Let this commencement be the occasion for reaffirming the principles off American Democracy . . . liberty and equal rights for all; regardless of color, creed, or national origin."

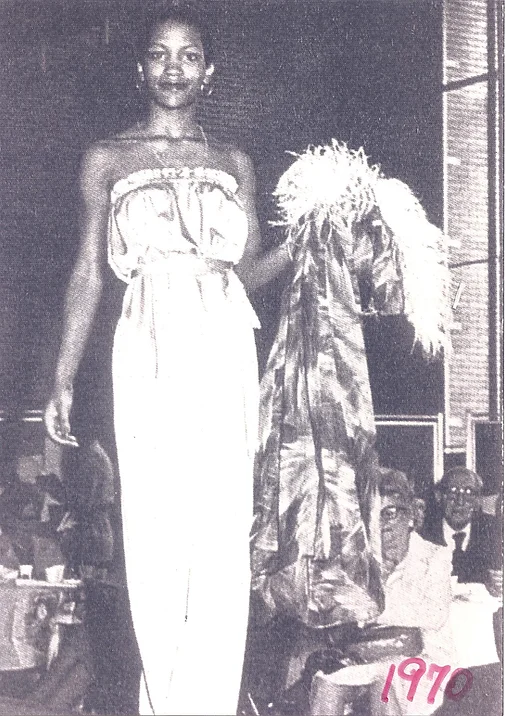

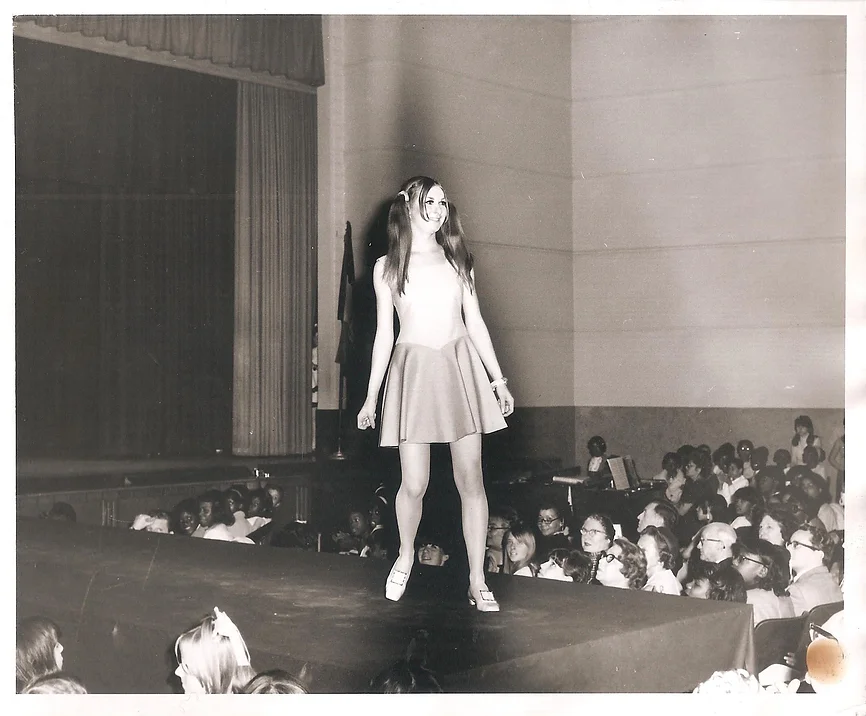

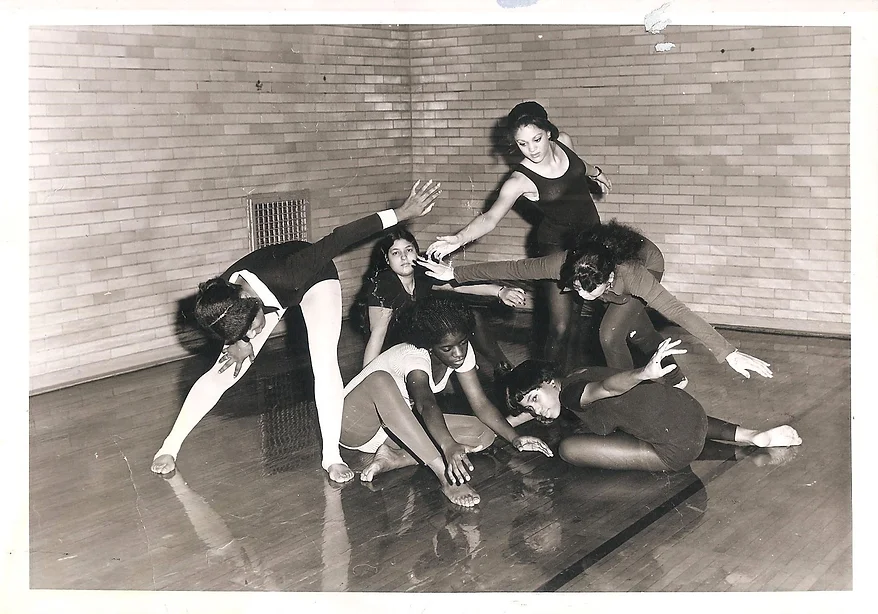

From the 1950’s to the present day, the school and its curriculum evolved. Seeing this, Principal Nathan Brown petitioned to have the name of the school changed. In 1956, Central Needle Trades became Fashion Industries. Over the years, the school has thrived and adapted, with dedicated teachers using instruction to help students comprehend the AIDS, Crack and COVID epidemics; the war in Vietnam and the terrorist attacks of 9/11; and social changes brought about by Women’s Liberation and the Civil Rights movements, and the technology revolution.

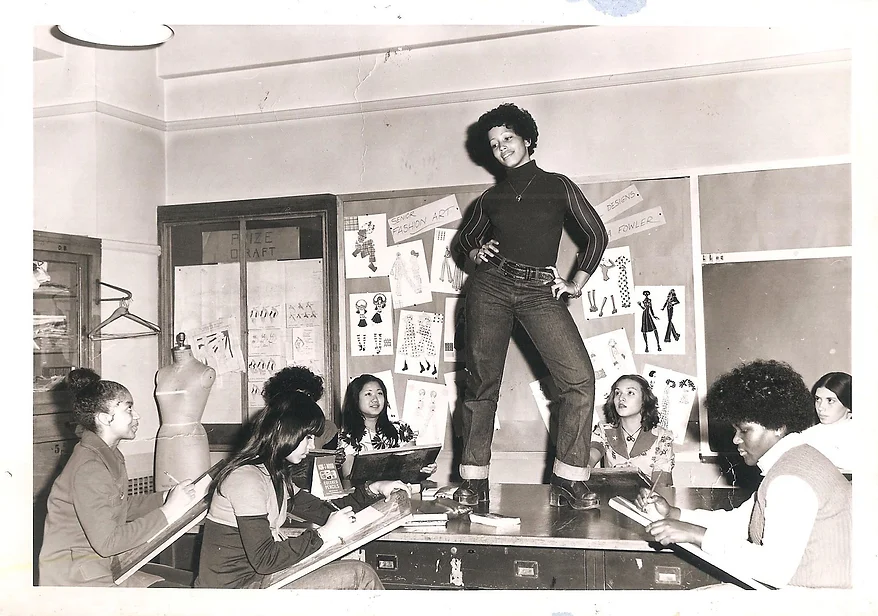

Beginning in the 1980’s, the curriculum underwent fundamental changes with an increased emphasis on academics and college preparation while maintaining its initial mission to provide a work force for the garment industry. And, as that industry has changed from one of manufacturing to one of design, marketing and merchandising, so have the offerings of the school, all now state certified as Career and Technical Education majors.

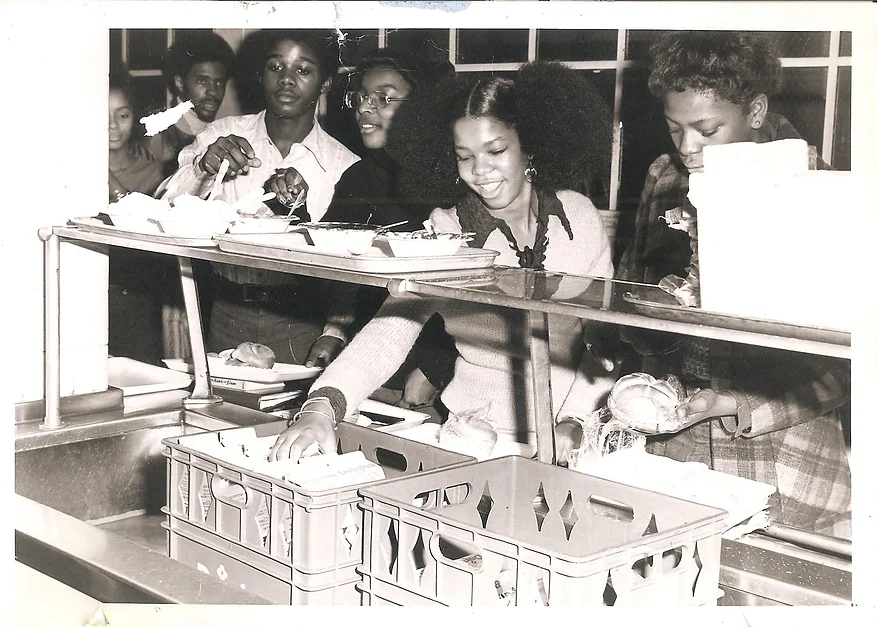

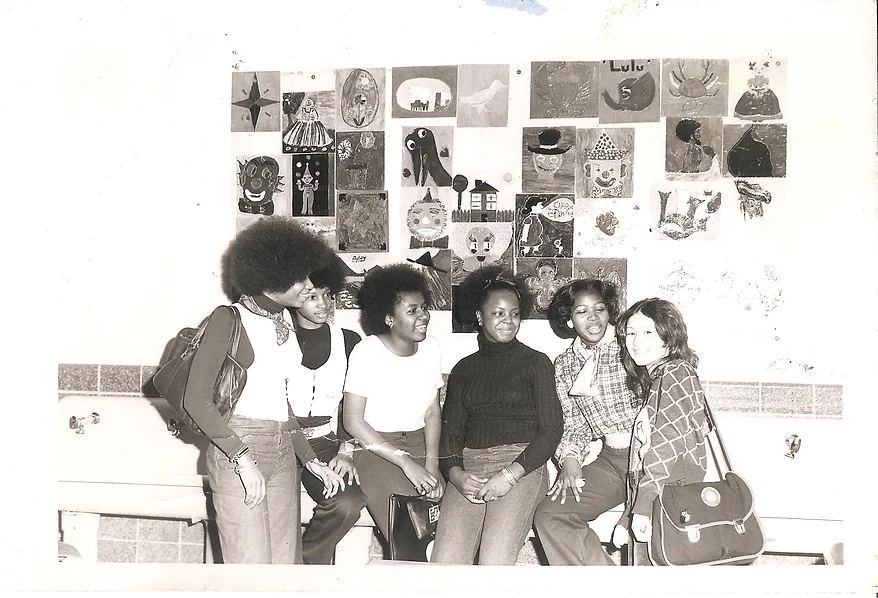

The student body has also changed, along with the population patterns of New York City. After World War II, there was an influx of African-Americans, part of the Great Migration from the South to the cities of the North and West. From the 1960’s through the present day, the school has continued to welcome immigrants from all over the globe. Like their predecessors when the school opened, they look to fulfill their dreams through careers in fashion.

By Charles Bonnici (Principal 1990-2012), based on his forthcoming book, The Skyscraper School